Shareholder loans, home loans and the time value of money: Comparing the alternatives

Business owners regularly face the challenge of extracting profits from their companies in the most tax-efficient way. While there are a number of different ways this can be achieved depending on your circumstances, two common approaches are paying dividends upfront or loaning funds out as a compliant ‘Division 7A’ shareholder loan. While upfront dividends can create an immediate tax liability (net of any franking credits), Division 7A loans defer tax payments but can result in higher cumulative taxes over time. This article compares these options, focusing on the after-tax cashflow outcomes to help you understand the factors to take into account when considering these alternatives.

Home loans and prioritising repayment

For many business owners, their home loan represents their largest personal expense outside of their business. Surplus profits are often distributed to owners (as dividends or otherwise) with the objective to pay down the home mortgage as quick as possible. It can be a sensible strategy in the absence of alternatives.

Since their home loan interest is a personal expense, the interest costs are typically not tax-deductible.

Division 7A and shareholder loans

Accountants often emphasize the importance of Division 7A compliance, and for good reason. The Division 7A rules are designed to prevent shareholders from extracting profits or assets from private companies tax-free. Borrowing funds from a company is allowed under tax law, provided the loans comply with the Division 7A rules.

While there are many different scenarios that could be considered, typically, when a shareholder borrows from their company under a compliant Division 7A loan and uses the funds for personal reasons the following tax implications arise:

The company includes annual Division 7A interest in its taxable income (subject to a 25% or 30% company tax rate depending on the business size)

The shareholder cannot deduct the Division 7A interest expense in their personal tax return

The annual principal and interest repayments are often made via the company declaring franked dividends to the shareholder, which are offset against the loan balance owed. In this case, no cash repayments are typically required, but the shareholder must pay tax on the dividends received, less any benefit from franking credits.

While spreading tax liabilities over several years may appeal to some business owners, Division 7A loans can create incremental tax costs compared to the upfront dividend alternative.

Failure to comply with Division 7A rules could result in the loan being deemed as an unfranked dividend, triggering significant additional tax liabilities. Therefore, it is crucial to properly structure and administer these arrangements.

Comparison of cashflows over 7 years

Consider a business (or investment holding entity) that earns $3 million in pre-tax profit in its early years of operation. The company has no external bank debt and the owner has no desire to take on any. The owner wants to withdraw their hard-earned profits to put into their home loan offset account.

Annual principal and interest payments on the shareholder loans are often settled by the payment of franked dividends to the shareholder (i.e. no cash repayments are required).

It’s important that these dividends are declared and documented correctly to ensure they can be validly offset against the obligation of the shareholder to make the loan repayments to the company so that the loan repayment is respected for Division 7A purposes.

In this example we assume the following to model the outcomes over a 7 year period:

The business owner leaves $900,000 in the company to cover company tax payable on the $3,000,000 profit (30% tax rate used for ease) and withdraws $2,100,000 cash from the company into their home loan offset account at the end of June 2024. This withdrawal is accounted for as a loan owed by the shareholder to the company in the business accounts for the 30 June 2024 year

The ATO Division 7A loan interest rate is 8.77% (assumed constant)

The owners have a home loan interest rate of 6% (assumed constant)

The shareholders are subject to marginal tax rates (i.e. up to 47% including Medicare levy) and have no other income or deductions

The $2,100,000 provides immediate interest savings on the home loan at 6% per year from July 2024

Two scenarios are considered:

Scenario 1: Upfront Dividend declared in the 30 June 2025 year

The $2,100,000 amount owed by the shareholder to the company at the end of 2024 is repaid via offset of a fully franked dividend declared in the 2025 financial year. The shareholder pays personal tax on the $2,100,000 dividend at marginal rates (net of any franking credits). This additional tax is paid using funds in the home loan offset account.

Scenario 2: Division 7A Loan

The shareholder puts the $2,100,000 loan under a complying Division 7A agreement and repays it over 7 years (with interest) via annual franked dividends. Taxes over this 7 year period are also paid using funds in the home loan offset account (i.e. reducing the interest savings).

For the purposes of this example, we have used a typical unsecured 7 year term Division 7A loan. A 25 year loan term may be available where the loan is able to be secured by a mortgage over real property with a particular value. In this case, a different after-tax cashflow outcome would arise because the annual minimum repayments required under the 25 year loan would be less than that of a 7 year loan.

Illustrative outcomes

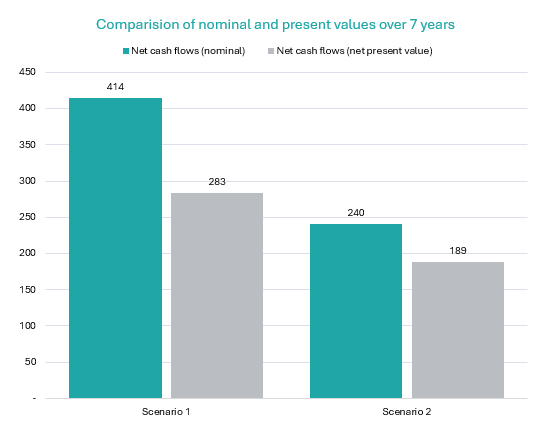

The following charts illustrate the cumulative after-tax cashflows for each scenario (numbers rounded to $’000’s).

Scenario 2: Division 7A Loan

Here, higher interest savings are achieved in the early-to-mid years due to interest compounding on a higher upfront offset account balance.

Tax liabilities are also spread over 7 years as the interest and principal repayments on the loan are repaid through the offsetting of annual franked dividends to the shareholder.

However, the taxable Division 7A interest income to the company (as the lender) and the corresponding non-deductible interest expense to the shareholder (as the borrower) adds incremental tax costs over time.

Scenario 1: Upfront Franked Dividend

In this scenario, the full dividend amount is taxed upfront (personal tax less any franking credits is paid in the 2026 financial year). While the tax hit is significant in the early years, cumulative cashflows recover steadily due to ongoing home loan interest savings that compound over time.

As there is no Division 7A interest income earned by the company, there is no additional company tax paid under Scenario 1.

Total cashflows over 7 year period:

Total home loan interest saved: $920,260

Less: Company tax paid: ($239,474)

Less: Personal tax paid: ($440,374)

Net cash benefit/(cost) $240,411

Total cashflows over 7 year period:

Total home loan interest saved: $895,050

Less: Company tax paid: ($ -)

Less: Personal tax paid: ($480,667)

Net cash benefit/(cost) $414,382

Given the high dollar amounts used in this example ($2,100,000), the owners are ultimately subject to the highest marginal tax rate bracket (45%) in both Scenarios (i.e. either upfront, or over the 7 year period under Scenario 2). In both scenarios, a time lag has been applied to the first-year tax liabilities to reflect the company and shareholder not yet being subject to the PAYG instalment system at that time.

While both scenarios achieve interest savings on the home loan, Scenario 1 produces a higher cumulative after-tax cash benefit over the 7-year period. Put this another way, financially, you would be better off paying the upfront tax by withdrawing funds out of your offset account at 6% interest per year rather than paying the ATO a higher amount over time.

“A dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow...”

Taking into account the time value of money

When comparing these two options, it is important to not only consider the total cashflows but also the time value of money through a net present value (NPV) analysis. This is based on the idea that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar in the future due to its potential earning power. Working out the NPV provides a clearer comparison by discounting future cashflows back to today’s value.

The discount rate used in NPV calculations typically reflects the shareholder's ‘cost of funds’ (or ‘opportunity cost’ of their money). Generally, this would be their business’s return on equity (i.e. what returns they could make by reinvesting capital back into their business) but could also be an expected return from other investments. In other cases, the business owner’s opportunity cost of funds will often be the interest rate on their home loan.

In our simple example above, using the home loan rate of 6% as the discount rate confirms that Scenario 1 remains the better choice in both nominal and NPV terms as per the adjacent chart (i.e. deferring the tax payable in Scenario 2 is not providing a benefit in NPV terms).

Other investment scenarios

Looking at both the nominal and present values is also useful when considering whether to use the company funds to make other investments that may need to be held in a separate entity structure for various reasons. It is often optimal to continue to make those investments through company structures, such that the funds don’t need to be extracted and give rise to Division 7A issues. However, if under the circumstances the funds had to be extracted such that Division 7A would otherwise apply, an equivalent analysis could be undertaken to the home loan example above to compare the impact of the how much capital could be invested into a new project, depending on how the funds are extracted from the company in order to fund the investment (e.g. as a dividend vs Division 7A loan). An NPV analysis here would take into account the timing of these different cashflows and tax liabilities.

What does this mean?

The above examples can illustrate that when the opportunity cost of funds is high, deferring higher tax through a Division 7A loan may align better with a business owner’s financial and commercial objectives. When the opportunity cost of funds is low, however, then it may be cheaper to bite the bullet and pay the tax upfront. A choice between the two will ultimately depend on the business owner’s circumstances and financial objectives.

Summary

While the above examples are illustrative (and simplified), they highlight the need for business owners to take into account the timing of the tax payable together with their cost of funds when considering the alternatives for extracting profits from their business, and what may suit them based on their circumstances.

There are valid reasons for choosing either approach. Scenario 2 may appeal to business owners who need upfront cash for urgent needs, such as funding a home deposit or reinvesting in a high-return project. However, this can come at the cost of compounding tax liabilities over time. Scenario 1 involves a larger upfront tax payment but may deliver greater net financial benefits over the long term, especially when the opportunity cost of funds is low.

An analysis should be done to compare both outcomes in nominal and present value terms in order to be sure you are considering the highest and best use of your funds and maximising your after-tax net wealth.

More information

The above information and analysis is provided for example purposes only and does not constitute financial or tax advice. There are many factors to consider based on individual circumstances. Please reach out to us if you would like to discuss your specific circumstances in more detail.

Notes

[1] There may be cases where the interest is potentially deductible under these arrangements, but that is not the focus of this article.

[2] In this example, a 30% company tax rate has been used to keep the analysis simple. However, the logic applies equally for small businesses eligible for the lower 25% company tax rate (i.e. typically those with sales turnover of less than $50m). Marginal tax rates have been used to model the tax paid by the shareholders (including the 2% Medicare Levy).

[3] Given the dollar amounts used in this example, the owners are ultimately subject to the highest marginal tax rate bracket (45% plus 2% Medicare Levy) in both Scenarios. Lower dollar amounts may result in different outcomes where the owners are subject to lower marginal tax rates for Scenario 2 vs Scenario 1 (e.g. if the annual minimum repayment required for Division 7A purposes is lower).

[4] The ATO publishes the annual interest rate that must be charged on Division 7A loans (called the “benchmark interest rate””) which references the interest rate for 'Housing loans; Banks; Variable; Standard; Owner-occupier’ published by the RBA. The current Division 7A interest rate of 8.77% for the 2025 financial year has increased considerably since 2022 consistent with global interest rates. The following is a summary of the historical Division 7A interest rates from 2021-2025:

30 June 2025: 8.77%

30 June 2024: 8.27%

30 June 2023: 4.77%

30 June 2022: 4.52%

30 June 2021: 4.52%

[5] For modelling purposes, the interest savings have been allowed to compound over the 7 year period to reflect the assumption that the benefit of the annual savings in interest would add further amounts to the offset account each year which then saves more interest in the following year.